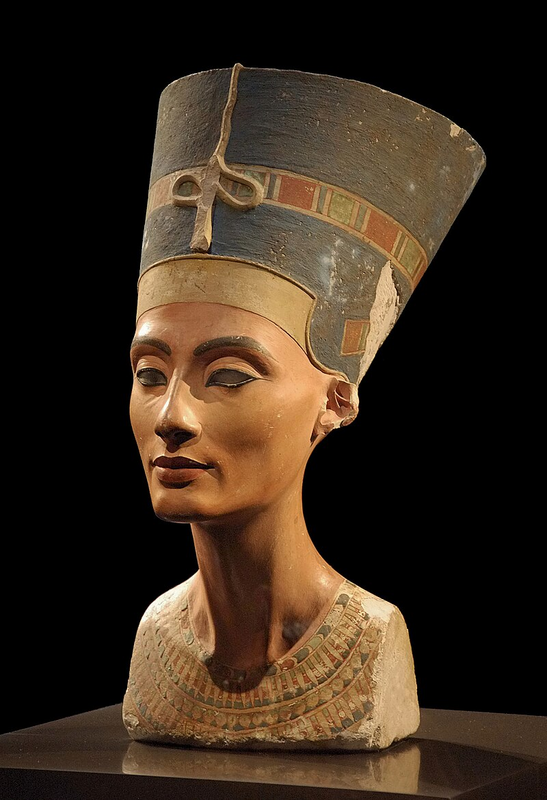

Hello everybody who visits this forum!! 🙋♀️ Does anybody know who this is:

📸️

I will give a hint: it was in a forum for @Sarahsalah27 almost a month ago: https://penpal-gate.net/forum/13-anything-and-everything/10805-the-test-of-osiris

If you dont know maybe you can guess BUTTT you cant look it up on Google!!!! And do you like the statute or not? 🙂

That's the famous bust of Nefertiti. The bust is famous with not its enigmatic aesthetics only. There is a roundaboutedly long story behind the beauty and the worth. At the time of Borchardt’s excavation, non-Egyptian archaeological missions were entitled to claim and export half the artefacts, or ‘finds’, recovered during each season’s excavation. Sharing of the finds was closely monitored by Egypt’s Antiquities Service, with an official ‘division of finds’ designed to ensure that no items of great archaeological or commercial value left the country. On 20 January 1913, the French Egyptologist Gustave Lefebvre, the antiquities inspector for Middle Egypt, agreed to the division of the Amarna finds. Borchardt had listed his discoveries, splitting them into two find lists of equal value. One was headed by a small carved scene showing Akhenaten, Nefertiti and their family sitting beneath the rays of the Aten. The other was headed by the Nefertiti bust. Inexplicably, Lefebvre selected the scene for the Cairo Museum, so ownership of the Nefertiti bust, and all the other artefacts on that list, fell to the aforementioned James Simon, official holder of the Amarna concession. On 7 July 1920, Simon donated his entire collection to the Neues Museum in Berlin, transferring ownership of the Nefertiti bust to the State of Prussia.

To many, Lefebvre’s failure to select the Nefertiti bust for Egypt is so inexplicable that it cannot have simply been the result of indifference or incompetence. Claims that Borchardt abducted Nefertiti have been so rife that even in Germany many accept that the bust was stolen.

It is particularly striking that the official division protocol listed Nefertiti as a ‘bust in painted plaster of a princess of the royal family’. It is not clear who created this description, but it contains two obvious errors. It is odd that Nefertiti is listed as a princess rather than a queen. The fact that the bust is described as being made of plaster is more significant. The outer layer of the bust is indeed plaster, but its core is limestone. In my opinion and experience in this field, it was not a simple mistake but the piece was deliberately misdescribed.

While acknowledging that Borchardt had met all legal requirements relating to the division, Pierre Lacau, the head of the Egyptian Antiquities Service and a French veteran of the First World War, nevertheless asked for the return of the bust on the grounds that there had obviously been a mistake. Lacau withdrew Borchardt’s permission to excavate until Germany either returned the bust or agreed to arbitration.

In 1930, James Simon published an open letter addressed to the Prussian minister of culture, reminding him that the museum’s directors had promised that the bust would be returned to Egypt should the authorities ever request it. His letter was ignored.

In October 1933, Hermann Göring, Minister President of Prussia, agreed to give back the Nefertiti bust to King Fuad, to commemorate the anniversary of the king’s accession to the Egyptian throne. Hitler, however, disagreed and personally intervened to block Nefertiti’s return.

Shortly before the Red Army took Berlin in 1945, the bust was hidden alongside Germany’s gold and currency reserves in a salt mine in Thuringia. Five months later, the Allied forces captured the mine, and the bust passed to the Monuments, Fine Arts, and Archives branch of the Allied armies.

In 1946, in order to show the German people that the bust had survived the war unscathed, the US Army put Nefertiti on public display in Wiesbaden. That same year saw a request for the repatriation of the bust, addressed by the Egyptian government to the Allied Control Commission in Germany and reminding them that the return of the bust had previously been agreed, only to be thwarted by Hitler.

But this request was refused on the grounds that the commission had authority to repatriate only objects looted during the war. As Nefertiti had arrived in Berlin in 1913, this was a long-standing legal matter between the Egyptians and the Germans, and in the meantime Nefertiti should return to her prewar home. However, there was a further problem: by now, Berlin had become a divided city, and the Neues Museum lay in the communist-controlled eastern sector. In 1956, the bust was sent to West Berlin where Nefertiti was exhibited first in the Dahlem Museum and then in the Egyptian Museum. Not unexpectedly, the German Democratic Republic tried to claim the bust on the grounds that the Neues Museum was located in East Berlin. They were unsuccessful.

Following the reunification of Germany, the Nefertiti bust returned to the Neues Museum, home of Berlin’s Egyptian Museum and Papyrus Collection. There have been repeated requests for its return to Egypt. In 1984, for example, the ‘Nefertiti Wants To Go Home’ movement suggested that the bust be displayed alternately in Cairo and Berlin, while in 2005 Egypt appealed to UNESCO to resolve the dispute – but the German authorities have stood firm. Egypt’s Ministry of Antiquities (a successor to the Antiquities Service) continues to press for the return of the bust, to no avail. Nefertiti remains on display in Berlin.

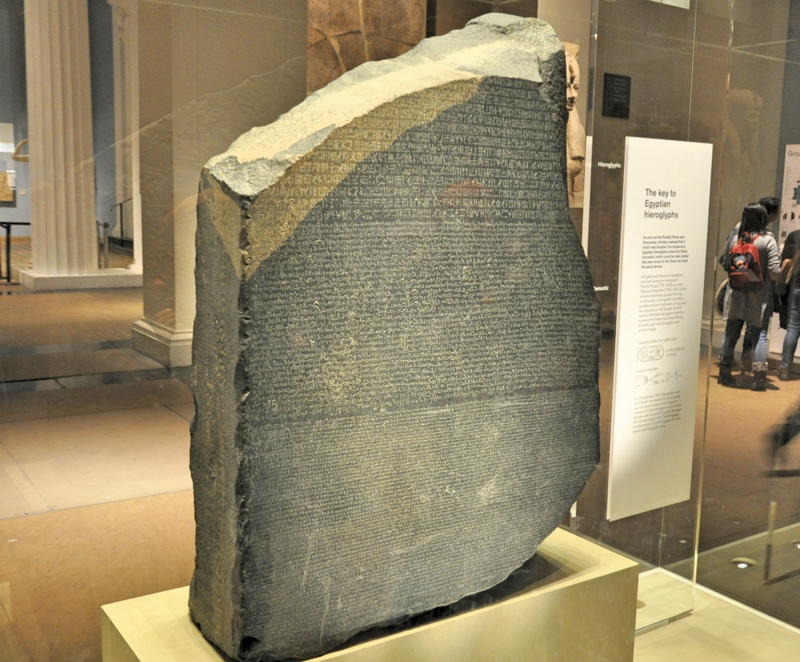

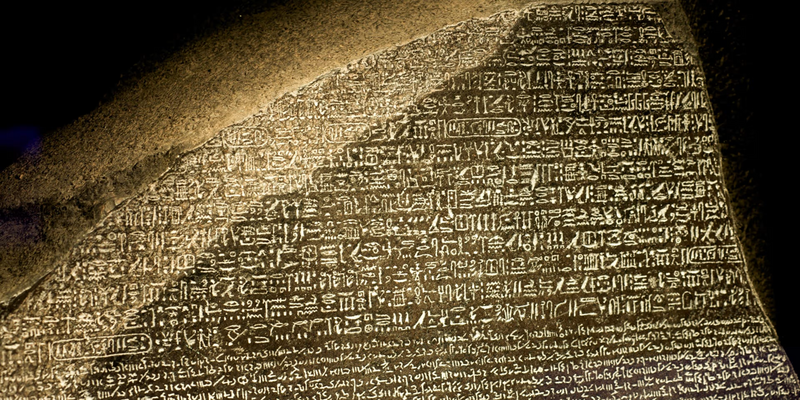

There is a similar story with Rosetta Stone or vast amount of ancient artifacts as well. General opinion among historians and archeologists, is that Artifacts harbored by museums should be repatriated as a means for restorative justice. While they may simply be sources of education or entertainment to some, to many others, they are of historical, cultural, and personal significance. However, there are still cases of museums refusing to return artifacts. They argue that there is no need nor necessity for artifacts to be returned to their countries of origin, mainly due to the lack of documented provenance and proper maintenance. For example, in May of 2013, the Archeological Institute of America estimated that nearly 85-90% of the artifacts in museums did not have documented provenance. This finding created a cloud of fear among most museums on the sudden rise in artifact ownership, and whether or not to accept countries’ legitimate claims over the objects. It is also the case that museums of colonialist powers, in comparison to developing nations, have extensive resources to better preserve historically and culturally significant objects. But these arguments nothing but a "cloud excuse" covering the main reason. There is also the bigger concern of private companies and museums that would lose financial opportunities from the loss of artifacts. Bigger names such as the British Museum, for example, made an estimate of about 4.3 million pounds just in 2019/2020, from their vast collections of artifacts during the colonial period.

Recent moves by some institutions to repatriate objects are positive, and point to a future where greater compromises may be met. While museums are always likely to need a large amount of storage space, it seems reasonable to think that less prominent items might be repatriated on a more regular basis, and that major items will be shared and loaned among the institutions that have invested in their maintenance and care.